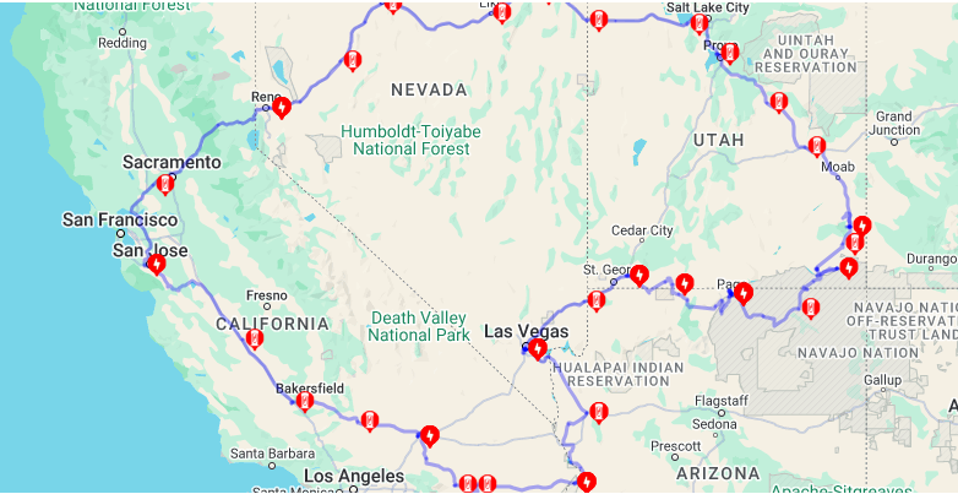

Map of an EV road trip. Lightning bolts are mostly hotels, Stalls are superchargers

Most of the debate on EV charging infrastructure focuses on the desire for fast charging stations, which recharge a car in 30-60 minutes. Up to $7B of federal money has been allocated to build those, though this may vanish with a recent executive order from President Trump. These stations have value, but it turns out that charging at motels is even more important, and it gets almost no attention. The issues around how to get charging at most hotels, how to make it convenient and how to price it are key issues for EV travel infrastructure.

Ideally, when taking a road trip, one stays at a hotel with EV charging which refills the car overnight while the driver sleeps. Such charging is vastly cheaper (in fact, often provided free to guests) and more convenient, as it involves no driving out of your way or time spent waiting—it happens when you sleep. The driver wakes up to a full, warm car and depending on their itinerary may do all their driving on that energy, or on hard-slog road trips, can at least get to lunch for a fast charge. In shorter range cars or very intense driving, they may use another fast charge before their hotel.

This is important because fast charging has become very expensive. It’s not unusual to see fast chargers costing 60¢/kWh. Tesla stations tend to be 40-50¢. It’s hard to make a business fast charging and that’s forced many providers to charge these very high prices. (The average cost of electricity in the USA is now up to 17¢/kWh, but depends on the state and time of day, ranging from 9¢ to 40¢.) Fast charging thus costs anywhere from 10 to 15 cents per mile, which is similar to, and sometimes more, than the cost of gasoline in average cars, and more than that for an efficient hybrid. EV owners definitely didn’t buy their EVs to pay more for energy than they did with gasoline cars.

Because hotel charging is often free to guests, that can make a big difference. For drivers going 400-500 miles/day, that means one hotel charge and one fast charge, and cuts the total cost in half. On a recent road trip I took of 2800 miles from California to Utah, the first half was slower paced, and the second half was a fast return home. I picked up 500 kWh at superchargers and roughly 300 kWh from hotels (all free except one hotel at 25¢/kWh.) That made my trip much cheaper, and about $200 less than in my old gasoline powered Acura TL, and of course, lower emissions. For the first half the trip, the ratio of hotel and fast chargers was about even.

Two Teslas charging at a hotel at Bryce Canyon National Park. The left one is keeping itself warm … More

I also gained from charging my first and last 200 miles at home from my solar panels. While that power’s already paid for, any power like this that I use rather than feed back to the California grid effectively loses me just 7¢/kWh. (Alternately, home solar at today’s interest rates costs about 10¢/kWh.)

Can it be Free?

My typical hotel charge was around 40 kWh. At the average Utah price of 11.4¢, that’s around $4.50 cost to the hotel. At the national average closer to $7. The value to me is much greater, because otherwise I will have to pay 40-60¢ at a fast charger, or around $20, plus a lot of inconvenience. This easily justifies going to a pricier hotel if it has charging, and you get all the other benefits of the higher-end hotel. But today we’re seeing many different pricing decisions by hotels:

- Free to Guests (fairly common)

- Low flat fee to recover costs, like $5 (rare) or metered at-cost (11-17¢)

- Low flat fee to recover costs and to reserve a stall (almost never)

- Premium flat fee ($25 to $40)

- Premium metered fee (25¢/kWh) similar to some public Level 2

- Super-premium metered fee similar to fast chargers (38¢/kWh)—becoming common

Many hotels are being pulled to the “minibar” style of pricing, a premium or super-premium price well above the ordinary retail price, because the hotel guest is a captive customer getting convenience. Those who do so can make a modest profit on charging, and also reduce contention at their stalls, as guests will no longer use the charging unless they truly need it. (It’s ironic that minibars often lose money even at their high prices and are mostly being removed from hotels.)

The more interesting dynamic applies to how guests choose their hotel. Today, EV roadtrippers are more rare—on this trip, outside of Las Vegas and Reno, we didn’t see another EV charging at these hotels, though the stalls in those Nevada cities were full and cars were turned away. Those EV roadtrippers who do look for it will always choose a hotel with charging over one without if they are even roughly comparable. They will choose a hotel with free-to-guests charging over one that charges premium fees, even if the former hotel is $20 more per night, for simple financial reasons—you get the free charge and a better hotel for the same total spend.

Today, almost all road trip hotels provide breakfast “free” to guests. Estimates suggest this simple breakfast costs the hotel around $4-$5 per person, or $10-$15 per room depending on occupancy. More expensive hotels often charge extra for breakfast but for the mid-range motorist hotels, free-to-guests breakfast is now a must-have feature in rural America. It costs more per room than charging, so that suggests we might get a world were free-to-guests charging is a standard amenity in order to get EV driving guests. At the same time, the minibar pricing plan is also growing in popularity.

There’s an irony that metered stalls cost a lot more than simple ones, so in many cases the premium fee is charged to cover the cost of being able to do billing. Many of the free-to-guests chargers are Tesla Destination Chargers, which Tesla provided free to many hotels. Tesla doesn’t forbid the hotel charging, but there was no mechanism so most don’t. (This is changing as Tesla now supports billing.) Even so, a fancy public station with credit card processing can cost 5 times as much, for the equipment, as a basic one, though the electrician can cost more.

One factor that could change this would be a facility for guaranteed reservations. Drivers want to be sure they can charge, though in most places today if they can’t, they just have to waste time at a fast charger, perhaps during dinner after they check in and see all stalls are taken. Drivers will likely be willing to pay reservation costs that cover the cost of the electricity, so the hotel gets that paid for while also winning a stay. At present, there are no systems for hotels to automate reservation of charging stalls, but this can come. Today’s option involves a hotel staffer putting a cone in a space or parking a car in one to hold it.

Guests will still stay at hotels with premium fees, but they will no longer consider them an automatic win over other hotels. As the EV transition progresses, there will be few hotels with no charging, the only question will be the price, whether a spot can be reserved, and if not, how many stalls there are. Hotels without charging will just not get any EV guests at some point, and be pushed to make the change. Fortunately, with modern power management, hotels can often install lots of stalls without boosting their electrical service, as long as power use in the hotel goes down at night, leaving capacity for the cars. (Disclaimer: I have an investment in a company which sells such tools.)

One possible pricing scheme, not in use today would be a combination price, such as a low ($5) flat reservation fee (or even free) for a typical charge of up to 40 kWh (around 160 miles) with reasonable per-kWh fees above that to recover costs on large battery cars.

Footnote: A large fraction of hotels have an exterior 120v dedicated plug they will let you use. Carry your adapter. It may seem of limited use to add only 50 miles (which is about all such a plug will do) but that means more time and options in the morning, and it’s like having a bigger battery. 30a RV plugs (different adapter) can give you 100 miles, which can make a real difference, especially if staying 2 nights.